Researchers from the Institut Pasteur de Montevideo and the Feinstein Institutes for Medical Research (USA) have identified a key protein linked to vascular anomalies (such as arteriovenous malformations) characteristic of a rare genetic disease that affects around 800 people in Uruguay and so far has no cure.

As part of the study -published in the scientific journal Nature Cardiovascular Research-, the scientific team also tested two drugs that, in the medium term, could be used to treat the pathology.

This is Hereditary Hemorrhagic Telangiectasia (HHT), a disease that affects the blood vessels, and in extreme cases can be fatal. Sufferers develop certain arteriovenous malformations, which cause abundant bleeding from the nose and gastrointestinal tract, which, in the long term, can lead to anemia. Arteriovenous malformations (abnormal connections between arteries and veins) can affect the brain, liver and/or lungs and, depending on the organ affected, lead to complications that can be very serious and even fatal.

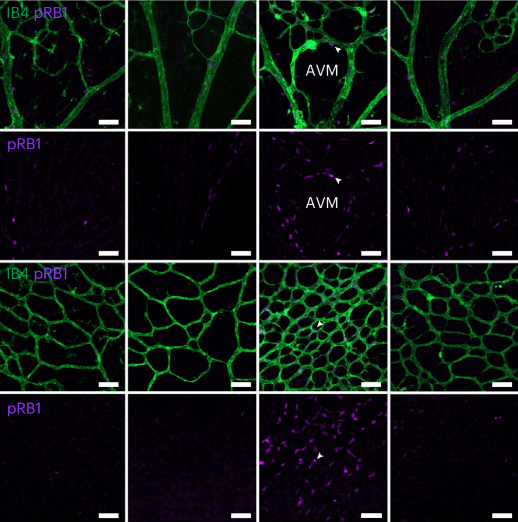

The arteriovenous malformations of HHT occur, among other things, because the cells of the blood vessels lose control and begin to multiply uncontrollably. The mechanism is similar to that which occurs in some types of cancer, when the cells lose control, proliferate uncontrollably and grow in size, forming a tumor.

In tests on mice, the research team found that, in the case of HHT, the CDK6 enzyme (a protein involved in the control of cell division) is responsible for this dysregulation.

During the tests they found that, in mice lacking the enzyme, they did not experience arteriovenous malformations and, therefore, did not develop the pathology.

Other studies have already evaluated the involvement of CDK6 in breast cancer, for example. Therefore, thinking of a future application in humans, the team looked for existing drugs that inhibit the action of the enzyme. In particular, they tested in mice with HHT two drugs used to treat oncology patients: Palbociclib and Ribociclib. In these tests, they observed that the HHT animals that received the medication reversed the arteriovenous malformations.

“In the medium term, drugs of this type could be used to treat HHT in humans. It is going to take several years of research and some punctual trials for patients to finally be able to use them as therapy,” said Santiago Ruiz, a researcher at the Laboratory of Metabolism and Aging Pathologies of the Institut Pasteur in Montevideo, who was part of the study.

“There is also the possibility that these drugs could be used in other diseases in which arteriovenous malformations occur whose development depends on CDK6 upregulation,” he added.

HHT in the world

Worldwide, the disease has a low prevalence (which is why it is classified as a “rare disease”) of one case per 5,000 people. Given the small number of cases, the general lack of knowledge makes diagnosis and treatment difficult. So far, HHT has no cure, and only palliative treatments are available.

Ruiz, in collaboration with other members of the Institute’s Laboratory of Metabolism and Aging Pathologies and physicians from the Pereira Rossell and Maciel Hospitals, have been studying the disease for several years.

The full study can be read here.