To complement the traditional detection of melanoma -the type of skin cancer with the highest mortality rate in Uruguay and in the world-, scientists from the Institut Pasteur de Montevideo, together with dermatologists from the Hospital de Clínicas (HC), developed an innovative molecular method based on advanced microscopy images which, based on the brightness of certain components of the sample, allows a more accurate diagnosis than the current one.

In practice, to identify melanoma, dermatologists use conventional microscopes that detect changes in the appearance of the tissue, which makes the diagnosis highly dependent on the specialist’s experience. Now, the new method will allow to have molecular confirmation that will help in a more accurate identification without human bias.

The work was published in the journal Frontiers in Oncology in its special issue “Advancements in Imaging Techniques for Understanding Spatial Heterogeneity in the Cancer Environment”.

It is also a contribution to knowledge promoted by a multidisciplinary team, led by Bruno Schuty, a member of the Advanced Bioimaging Unit (a mixed group of specialists from IP Montevideo and the HC), and Sofía Martínez, a specialist from the Chair of Dermatology at the HC, and led by Leonel Malacrida, head of the UBA. This unit, created in 2020, focuses on the development in Uruguay of cutting-edge technologies for scientific and medical imaging.

Shine to diagnose

The technology that made this breakthrough possible is spectral imaging, which focuses on the analysis of the electromagnetic radiation emitted by an object.

Unlike other imaging methods, spectral imaging uses a wider range of frequencies or wavelengths to create detailed and specific images. In Uruguay, this technology exists in several confocal microscopy instruments.

Applied to medical imaging, for example, it not only captures the anatomy of the sample, but also provides information on the chemical composition and density of the tissues.

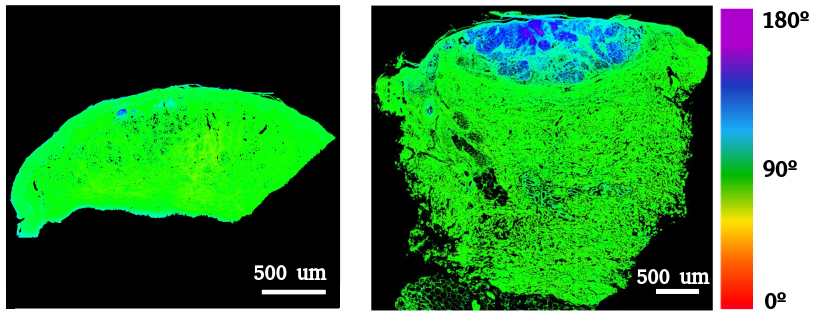

In particular, researchers from the UBA and the Chair of Dermatology used a spectral confocal microscope to analyze skin samples and observe molecules such as collagen, elastin and melanin, among others. These molecules are called autofluorescent, because they glow naturally when illuminated with certain types of light. This microscope focuses ultraviolet light on the sample which makes these molecules glow and reveals their different fractions in the tissue.

Thus, the researchers observed these molecules in a series of melanoma samples and detected color changes that are associated with specific characteristics. As a result, they noticed that certain changes in the proportions of these molecules present in the sample or modifications in the color are associated with the presence of the disease.

The natural brightness of these molecules is also a technical advantage, because it means that no staining or sample preparation is necessary. This facilitates its implementation in any dermatology center that has access to a spectral confocal microscope, which is an advanced but affordable piece of equipment.

Due to its accuracy and simplicity, this tool could be applied in the detection of other pathologies. In fact, researchers from Argentina and Mexico visited the UBA during these months to test this technique in oncologic pathologies of other organs and tissues.